COVID-19 and Sri Lanka’s External Sector: Challenges and Policy Choices – Institute of Policy Studies

The COVID-19 pandemic exerted significant downward pressure on global trade as well as the global economy at large. Unprecedented declines in merchandise trade, foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, tourism and cross-border migration have all been hallmarks of the economic fallout. As a result, growth expectations for countries worldwide dimmed. Nonetheless, thanks in part to substantial expansionary monetary and fiscal policies being rolled out to achieve pre-COVID economic recovery levels and the development of vaccines, the contraction in global trade and economic output are less than what was anticipated.

The Sri Lankan economy too has been impacted by these external developments, witnessing fluctuating fortunes in its external sector performance. This blog discusses the impacts of global economic developments on Sri Lanka’s external sector and suggests ways to cushion them.

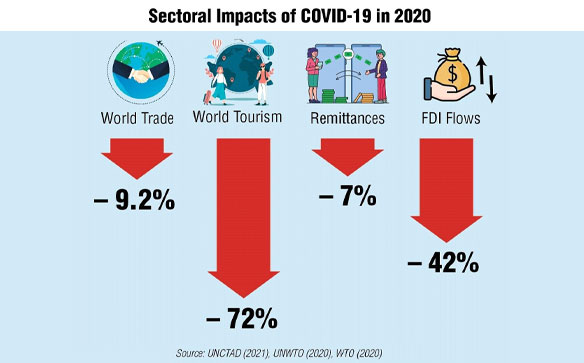

Sectoral Impacts of COVID-19

The impact of COVID-19 on global trade flows was substantial, contracting merchandise trade by -5.3% in 2020, albeit a much-improved outcome from the initial -12.9% forecast. As expected though, global FDI flows saw a sharp decline in 2020 contracting by 42% in 2020 compared to 2019. There have also been significant impacts on other forms of cross-border capital flows such as world tourism, migration and related cross-border remittance flows.

Even before the pandemic, Sri Lanka’s long-term export growth rate was on a declining trend, despite some improvements in the immediate pre-COVID-19 years. In 2020, the pandemic amplified this long-term decline. Merchandise exports contracted by –15.6% in 2020 compared to 2019, reflecting both demand and supply shocks.

Apparels, Sri Lanka’s major merchandise export, faced disruptions with the onset of the pandemic, with earnings from textiles and garments (T&G) falling by 21% in 2020. Furthermore, surveys suggest that as many as 89% of Sri Lankan apparel workers were temporarily retrenched from March-May 2020, with partial or no pay during the first wave of COVID-19.

Compared to exports, Sri Lanka’s import expenditures fell even more sharply in 2020, contracting by as much as –19.5%. A part of the decline was no doubt a reflection of weakened private investment, declining oil prices and subdued consumer demand. However, a large quantum of the drop in import expenditures is due to restrictions imposed on ‘non-essential’ imports and import-substitute sectors.

International arrivals to Sri Lanka declined by –73.5% in 2020. By contrast, Sri Lanka’s worker remittance inflows have performed much better than what had been forecast. In 2020, after an initial brief drop, remittances grew by 5.5% to USD 7.1 billion. FDI flows to the Sri Lankan economy have been on a declining trend over the years. The pandemic has amplified this trend, with inflows contracting by –43.6% in 2020 compared to the previous year.

Challenges and Choices

Sri Lankan exports traditionally target product markets in a few destinations such as the US, UK and some EU countries. Its export basket too remains rather limited, with overwhelming dependence still on T&G and a few agricultural products. The need to revive export performance with sound strategies such as export diversification and exploring new markets will take on even more urgency in the wake of the pandemic if the country is to build resilience to face such events in the future. The recent announcement by the EU to review Sri Lanka’s GSP+ status only adds to the urgency to strengthen domestic export resilience.

As countries adjust to the economic fallout of the pandemic, existing global supply chains will change. Sri Lanka too must be prepared to change direction in favour of strengthening such regional and global opportunities. Restricting imports should be viewed as a temporary solution; not only does it limit consumer choice, import restrictions also have other long-term costs. These include the possibility of tariff retaliation by trading partners, adverse impacts on domestic manufacturing for exporting, and resource misallocation. Though the dependence on import compression has facilitated an improved trade balance, increasing export revenue is a must to stabilise Sri Lanka’s external sector, including its exchange rate, in the medium to longer term.

Although Sri Lanka has seen an increase in remittances, weak employment conditions in migrant-hosting countries may cause an upturn in return migration. Thus, there is a need to formulate policy action in support of resettling, providing jobs, and facilitating business openings. Equally, retaining investors’ confidence through sound policy decisions, ensuring domestic security measures, and providing a transparent and accountable regulatory environment are essential to attracting more FDI. This is vital in view of the government’s stated policy intention to move away from debt-creating capital inflows to non-debt-creating sources. In the context in which Sri Lanka is struggling to access international capital markets in a COVID-19 environment, an enhanced inflow of FDI will provide relief on the external front.

However, Sri Lanka must be watchful that a growth recovery kick-started by FDI inflows is not solely dependent on sectors such as mixed development projects as the contribution of such activities to productivity-driven growth is minimal. In turn, the long-term sustainability of such a growth momentum is also in doubt. Secondly, as geopolitical tensions and rivalries heat up as countries race ahead to recovery, inviting FDI into strategic sectors such as ports and energy should be done in ways that safeguard Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and security.

*This blog is based on the comprehensive chapter on the external environment in IPS’ forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2021’ report.