COVID-19 vaccine passports: Positives and Pitfalls

As countries across the world, slowly but surely, begin to vaccinate their populations, discussions have sprung up surrounding the potential use of a COVID-19 vaccine passport. A panel discussion held by Mozilla, titled ‘Covid vaccine passports: the positives and pitfalls’ was held on 14 April, to analyse what the future may hold for this new kind of passport.

What is a COVID-19 vaccination passport?

First, the question arose as to what exactly a vaccine passport is and how it would be used in practice. Panellist Imogen Parker, Associate Director for Policy at the Ada Lovelace Institute, revealed that vaccine and immunisation passports are not an entirely new idea.

She said in the past, vaccination passports have been used for Cholera and Smallpox to limit the spread of those diseases. In practice, she pointed out that a COVID-19 vaccination passport would either be a physical sheet of paper, proving that the holder has been immunised against COVID-19, or a digital application that contains similar information.

The purpose of a vaccination passport is to allow people to move about safely and to provide information about the vaccination status to those who require it. Parker said this vaccination passport could be used for domestic purposes, such as for vaccinated people to enter public places like bars and restaurants. On the other hand, this passport could be used to facilitate international travel. If an individual wanted to travel abroad, they could do so by showing their vaccine passport at an international border to prove that they have been vaccinated.

Privacy

Unfortunately, the idea of COVID-19 vaccine passports has come under fire from groups claiming that these apps pose a dangerous threat to the right to privacy. Ultimately, the premise of vaccine passport is that someone else is being given access to your data.

The second panellist, Alice Munyua, Director at the Africa Innovation Programme, Mozilla, pointed out that a COVID-19 vaccine passport would contain notably more data than any other vaccine passport previously to be used.

The yellow fever vaccine passport was only a sheet of paper, she said, but a COVID-19 vaccine passport would likely contain swathes of personal medical data, including biometrics, medical histories, and maybe even medical histories. She alleged that when profit-based incentives become the forefront of any project, the goal of protecting people often gets sidelined. More must be done to scrutinise companies and developers who simply want to get consumers to use their application and have little care for social safety.

Parker chimed in by saying that this level of breach in privacy can have several real-world consequences. She said because different actors can view this data, it could impact an individual’s employment options or even insurance premiums. Those without vaccinations could face fewer job opportunities and higher insurance premiums due to a higher risk of hospitalisation.

Additionally, she said governments will likely have access to this technology even after the pandemic. Parker used the example of the 9/11 attacks and the ensuing crackdown on privacy in America. She said countries must be careful not to fall into a similar trap.

Inequality

Questions were then raised about how the implementation of such a programme would affect countries that have struggled to inoculate their populations. The third and final panellist, Dr. Pamod Amarakoon, a vaccine certificate expert at the University of Colombo, noted the difficulties in Developing Nations to adapt to a vaccine passport programme.

He said in Sri Lanka, instead of storing the data within the application, developers are looking into using a combination of paper-based passports and digital passports. An example he gave was being able to use a QR code which shows an individual’s vaccine card.

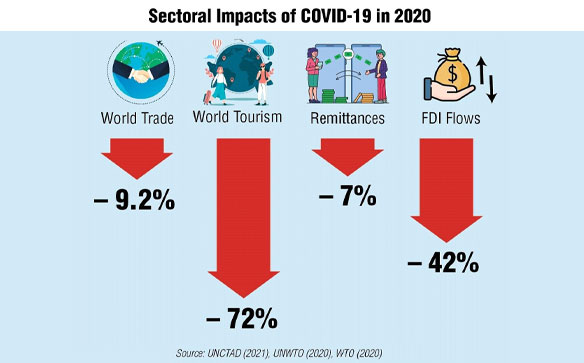

However, despite this, several issues were expressed by the panel, relating to a global implementation of a vaccine passport programme. Munyua said while the West has begun vaccinating quickly, some poorer African and South American countries are yet to reach that standard.

She pointed out that this could lead to a splintering of the world, as many developed countries would be able to open their borders as developing countries may not. This could exacerbate existing geopolitical inequalities, she added.

Additionally, Munyua feared the rise of vaccine nationalism. She saw a possible future where some countries only accepted vaccines that were approved within their own borders. Unless there was international cooperation or agreement, a vaccine passport scheme could lock out many poorer Nations.

Worth the risk?

Parker acknowledged that a vaccine passport system may end up saving lives by preventing the spread of COVID-19. “The justification is that since you pose a risk to me, I deserve to know if I am safe or not,” she said.

However, Parker also made it clear that science is still evolving, especially regarding transmission of COVID-19. “It’s not a question of privacy versus saving lives,” Parker said, stressing that a vaccine passport system should be efficient to save lives and for now, experts are conflicted if vaccinations will prevent transmission.

Dr. Amarakoon said if development were to go ahead, a central body should be set up to monitor the passports. He added that developers must be careful with who collects the data, where the data is stored, and what kind of data is collected

in the first place.

It is important that everyone involved in development and implementation of such a plan is aware of what exactly this passport system is meant to solve, Parker said. Existing legal and ethical frameworks should be understood, and Parker said it is vital that those rules are followed.

It is also important that the public is consulted whilst in development. The New York City application does not work on older phones, making it partially ineffective. These issues should be avoided.

Most importantly, Parker advocated for sunset clauses that mandates that after a given time, the State should no longer have access to this data. This way, governments and companies would inevitably be forced to stop collecting this data.

If vaccine passports are to go ahead, they should be done thoughtfully, with equality and privacy concerns at the forefront of development.